The paradox of choice in capitalism is driving us (almost) crazy

How we can be, ironically, paralysed by flexibility and abundance in life

Welcome to SEArcularity! If you’re new here, you can join our community of 160+ subscribers and receive our weekly circular economy newsletters in your inbox.

Ah, the abundance of choices

Capitalism promises us freedom through the abundance of choice—but in practice, this "freedom" often becomes a trap.

Barry Schwartz is an American psychologist and author.

He researches the link between economics and psychology; morality, decision-making, and the inter-relationships between behavioural science and society.

In one of his best-selling books, The Paradox of Choice, he explains why the explosion in consumer choice has, ironically, made us collectively miserable.

We value the sense of freedom so highly, it becomes counterintuitive that an increase in freedom leads to a decrease in satisfaction. And, often, that's the case for us.

Understanding this concept, I learnt that this isn't just a personal dilemma about which life path to take.

It's a structural feature of consumer capitalism, one that shapes our daily experiences, our anxieties, and even our sense of self.

Barry Schwartz nailed it in his book. He emphasises that every choice comes with its own opportunity cost.

An abundance of options doesn't free us from difficult decisions, after all—it makes every decision difficult.

I'm sure we've all experienced this.

Try buying a winter jacket and you'll face a dozen different options. Each model has pros and cons. No single brand stands out head and shoulders above the others.

The more you study your options, the more you struggle to make a decision. No matter what you choose, you'll face a tradeoff.

Comfort vs aesthetics. Price vs quality. Brand appeal vs practicality.

Instead of being happy with any option because they're all good, you can only think about what you lose by not choosing the others.

Extend this plethora of options to literally every aspect of our lives, and you begin to grasp the scale of choice paralysis we're dealing with.

Personally, given that our conscious brain can only process a fraction of the gazillion amount of information we receive each day, I believe that we literally aren't designed to handle this abundance of choices.

Why we were not designed for optionality

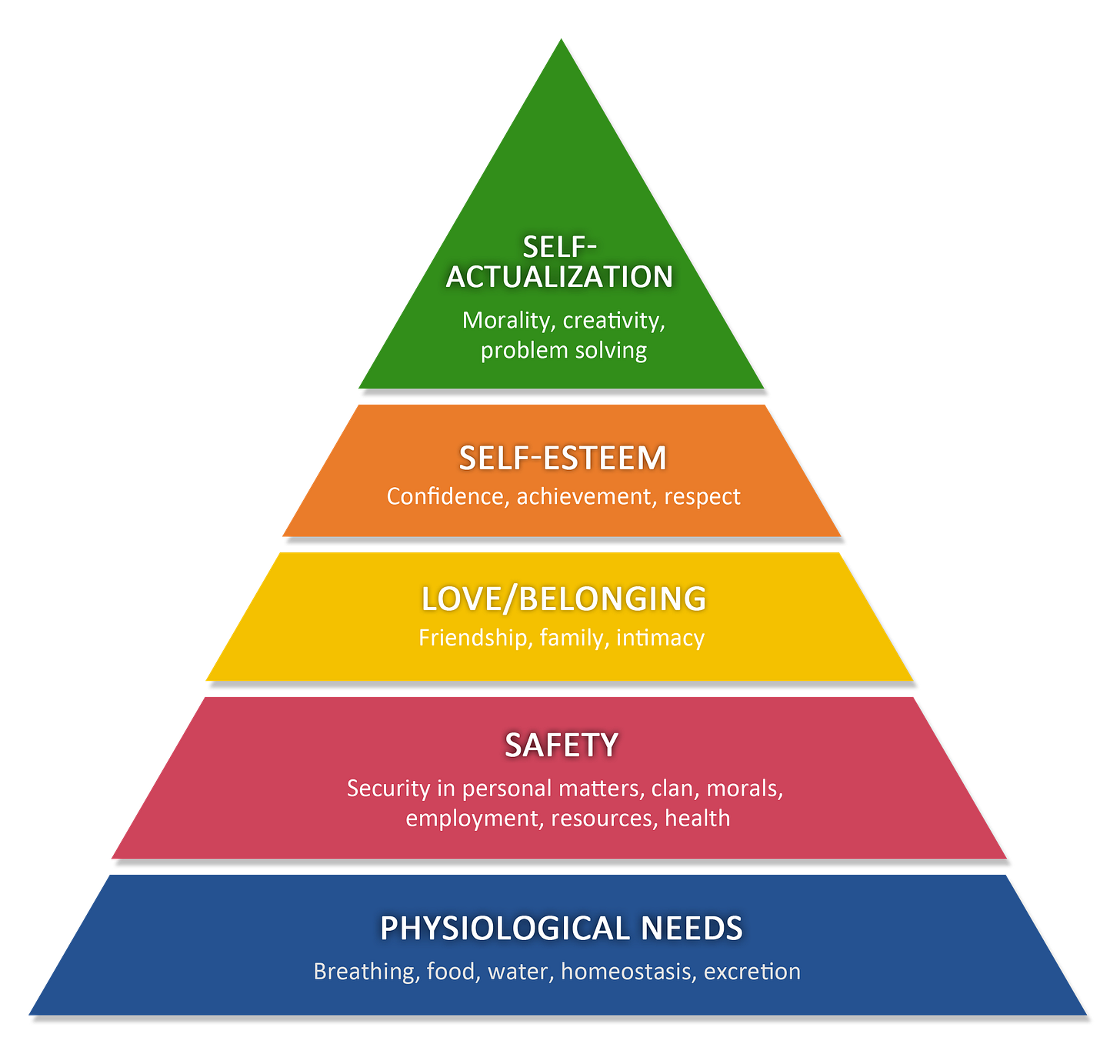

For most of human history, 90% of our time was spent trying to satisfy the bottom levels of Maslow's hierarchy (no real source, just a personal hunch).

Early hunters and gatherers drifted around as groups, spending every waking moment tracking prey, preparing meals, constructing shelter, or providing for the youth.

We operated within our individual bubbles. You worked, married, and lived within your community alone.

Suddenly, the internet changed everything. Suddenly, the knowledge base of the world was at our fingertips.

The physical boundaries that separated our millions of worlds showed up, and the world became a massive, interconnected network of information and opportunity.

The internet turned thousands of years of evolution and societal development upside down in a single generation.

And we weren't ready for it.

Is there a problem with optionality?

What we do, who we build relationships with, where we live—the possibilities in every aspect of our lives have been permanently expanded by a degree of the umpteenth power thanks to the internet.

We're no longer limited by our geographic boundaries. We're paralysed by a plethora of options.

The greatest rewards, paradoxically, come from the strongest commitments. From minimising one's flexibility. From going all in.

The best athletes in history: Kobe Bryant, Serena Williams, Usain Bolt — they all had an obsession in self-mastery and perfecting it.

There's no diversifying or Plan B. They quite literally put all their life into it. It was go big or go home.

The best of the best do not value flexibility and "keeping the options open."

They aggressively remove everything from their lives that could possibly hinder their successes and their main goal.

It has played out in my own life, too

When I hit my mid-20s, I found myself in a good position: enough money to settle down, but also the ability to choose adventure. I chose adventure. I moved to Spain to pursue a master's in sustainability; seeking purpose over predictability.

But with every new freedom came a new burden. After graduation, the questions multiplied: which job, which country, which lifestyle?

Should I chase the digital nomad dream, or follow the latest Instagram-fuelled travel trend? Should I go to the Balkans, or Africa, or just focus on my career?

Yes, this is probably an existential privilege—but it's also capitalism's endless optionality.

When every path is open, every decision becomes fraught with opportunity cost, regret, and the fear of missing out.

Capitalist culture is relentless in its messaging: your life isn't enough—do more, buy more, travel more, become more.

If you see that paddle is a trend in Jakarta and KL, do it. If your baby cousins have Labubu, maybe you should too.

The result is a constant sense of inadequacy and restlessness, a feeling that whatever we choose, we're missing out on something better.

This isn't accidental. It's the engine of consumerism.

Social media and algorithms amplify this, feeding us curated visions of what we "should" want, turning even our desires into products to be compared, optimised, and consumed.

About opportunity cost and the myth of infinite freedom

Every choice comes with an opportunity cost.

In a world of infinite options, the cost of choosing one thing is giving up countless others—jobs, travels, relationships, identities.

This isn't just a personal struggle; it's a systemic feature of capitalism.

Our time, attention, and emotional energy are finite, but the market's demands are infinite.

The result? Chronic dissatisfaction, anxiety, and a perpetual search for the "most right" decision.

When you have an abundance of good choices, the problem is reversed.

You don't know what's "right" and "wrong" because every option is right.

The aftermath of these decisions isn't filled with gratification and relief—it's filled with doubt and thoughts of "what if."

We have infinite choices, but finite time. Dozens of paths, but only one body.

We live in a world driven by opportunity costs, and the opportunity cost of everything has never been higher than in our modern era of abundance.

It's maybe time to come home to ourselves

The abundance of options doesn't liberate us; it chains us to endless cycles of comparison, regret, and longing.

Real freedom may lie not in maximising our options, but in learning to say "enough," to commit, to unplug, and to reclaim our time and attention.

Capitalism doesn't just create the problem—it sells us the solution.

Feeling overwhelmed by choices? Subscribe to a curation service. Anxious about missing out? Buy this course on optimal living.

The system that creates our choice paralysis then profits from our attempts to escape it.

Faced with this overwhelm—exacerbated by global crises and the algorithmic churn of bad news—I found myself unplugging from social media, seeking refuge in slower, more intentional spaces like Substack.

Digital detox is an act of resistance against a system designed to keep us perpetually unsatisfied.

Because, honestly, the real answer isn't another purchase or another experience.

It's coming home to ourselves. It's recognising that enough already exists within us, not in the next shiny object or Instagram-worthy destination.

Maybe the most radical act in a capitalist society isn't choosing better—it's choosing less.

Fighting consumerism by finding contentment in what we already have.

Resisting the manufactured urgency to do more, be more, buy more.

The greatest things in life aren't valuable because of the optionality they provide—they're valuable because of the commitment they require from us.

Finding this relatable and secretly holding onto that overwhelmed feeling?

That's okay. Slow down and be easy on yourself.

I hope to come back soon to diving into circular economy policies and other technical stuff we discover about the industry—once I feel a bit more grounded and ready. Hopefully in a couple of weeks.

For now, though, maybe we all need to sit with the discomfort of having fewer answers and more questions. Sometimes that's exactly where the real work begins.

— Mutiara from SEArcularity

Thinking about this from the other end, as well. How to use our time at work to be more human, push businesses towards values. Great piece!